If the economy is going strong then why do we need interest rate cuts so desperately?

In these intriguing times, the landscape of the US economy ventures into uncharted territory. Who could have envisioned a scenario where the United States finds itself nearing full employment, while inflation hovers around 3%, all amidst a government engaging in a monumental spending spree?

When it all started

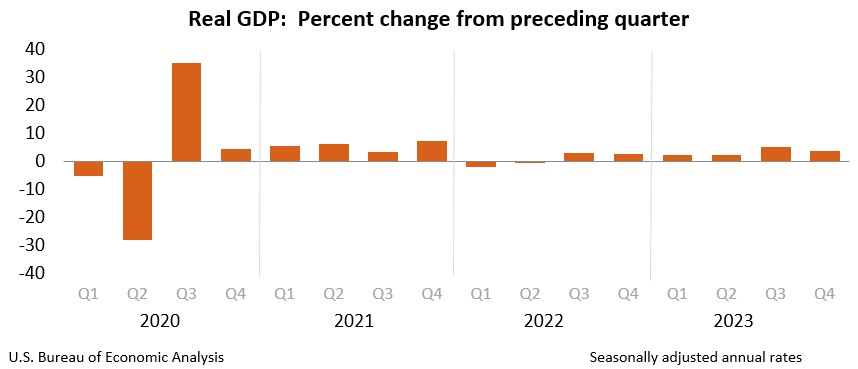

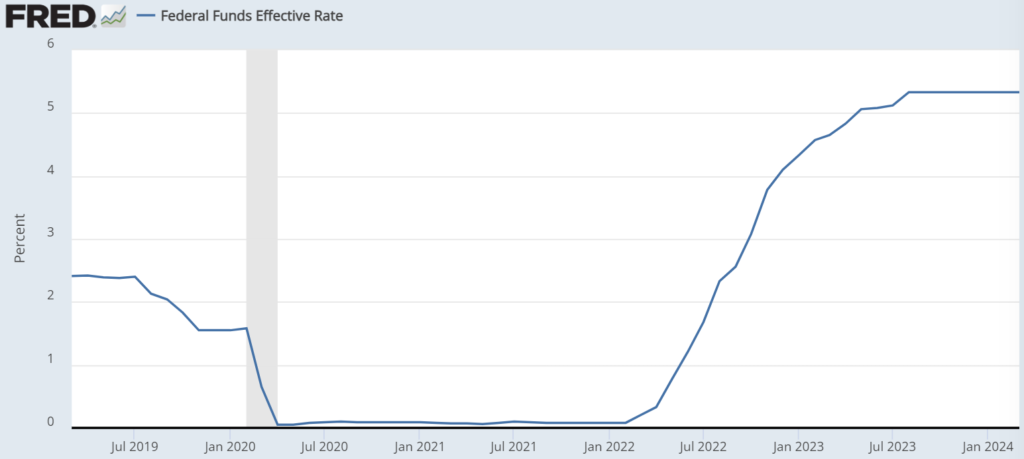

The Federal Reserve Board lowered interest rates to near zero in 2020. Benefited by the low-interest rate along with other relief bills, the economy has continued to heal throughout 2022 and 2023. Real GDP increased 2.5% in 2023, compared with an increase of 1.9% in 2022.

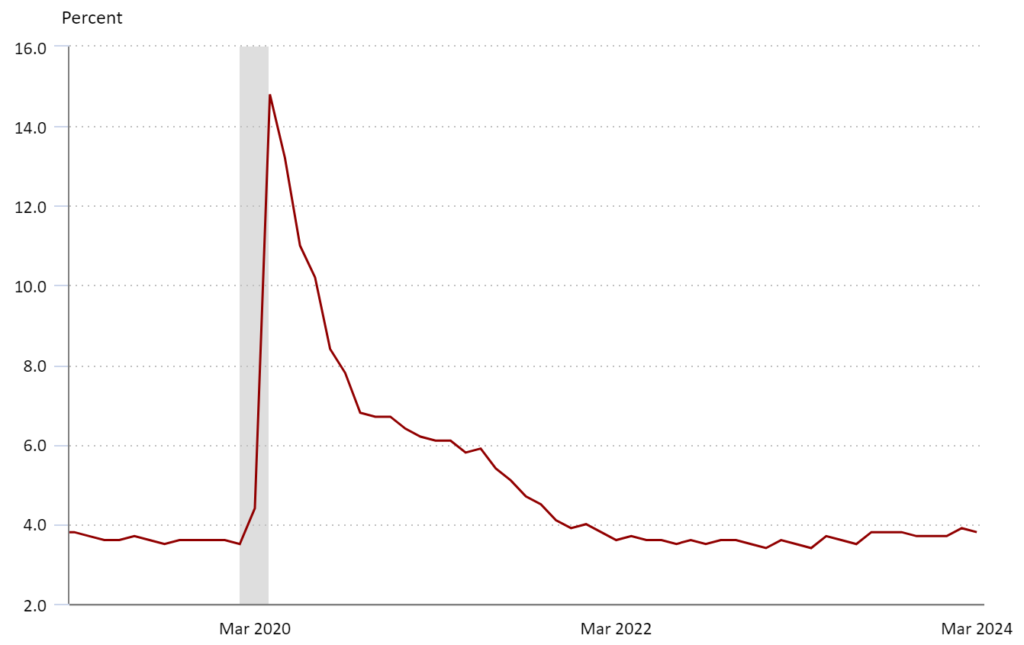

The unemployment rate has been running below 4% since January 2022 and has remained there since. By the end of 2023 job creation was well above and economic activity was slightly above their pre-pandemic projections.

This expansion was followed by high inflation, partly due to supply chain issues, labor shortages and economic expansion. Inflation started to rise in early 2021 and peaked in June 2022 when the 12-month measure of the consumer price index (CPI) reached 9.1%. The Federal Reserve then took steps to tighten monetary policy to bring inflation down and interest rates started to rise. The last rate hike occurred in July 2023. Over that one year period, the central bank raised the fed funds rate by more than 5 percentage points.

Why there is still strong growth even if the interest rates are high?

As the Fed raises interest rates, we typically expect slower economic growth. Surprisingly, however, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) grew more quickly in 2023 (2.5%) than it did in 2022 (1.9%). This is mostly attributed to the massive fiscal spending by the government since the Covid times. The government spending increased from $4.7T in 2019 to $7.1T in 2021 and is expected to be $6.5T in 2024. As a result, the economy continues to be resilient with strong consumer spending and wage growth.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics as of March 31, 2024.

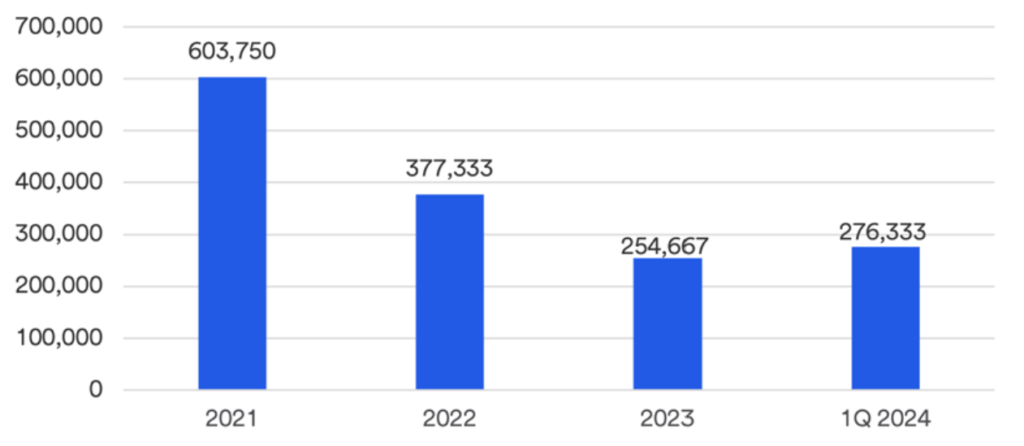

The U.S. labor market in March registered job growth for the 39th consecutive month, with payroll employment growing by 303,000. It was the largest monthly jobs gain in 10 months. The unemployment rate declined a bit, to 3.8%, but extended its streak of below 4% to 27 consecutive months, the longest month-to-month stretch of below 4% unemployment from 1967 to 1970. In March, average hourly earnings for all employees on private nonfarm payrolls edged up by 12 cents to $34.69. Average hourly earnings were up by 0.2% in March and 4.1% over the year.

The strong job market puts consumers in a position to maintain solid spending levels, keeping the economy growing in the face of persistent inflation and elevated interest rates.

Can the interest rates stay high for longer?

The prolonged maintenance of high interest rates can inflict significant harm on the economy across various sectors, as evidenced by historical occurrences and contemporary challenges. The two biggest challenges include bank stress and rising delinquencies.

Higer rates diminished the ability of individual and business borrowers to service their debt, known as credit risk. When interest rates remain elevated over an extended period, borrowing costs rise, making debt more expensive for both consumers and businesses. For instance, during the Volcker Shock in the 1980s, the Federal Reserve’s aggressive tightening of monetary policy resulted in a severe recession in the United States, characterized by high unemployment and financial distress.

Moreover, higher interest rates erode financial buffers, exacerbating vulnerabilities within the corporate sector. Businesses, especially small and mid-sized firms, may find it increasingly challenging to meet their debt servicing obligations as interest expenses escalate. Defaults in the leveraged loan market become more prevalent, signaling financial distress among weaker firms. The erosion of cash buffers also affects households, with excess savings declining and signs of rising delinquencies in credit cards and auto loans becoming apparent.

The longer-duration assets mostly in every major bank’s balance sheet also suffer a significant decline in the asset value. Beyond the banking sector, fragilities are also evident among nonbank financial intermediaries, such as hedge funds and pension funds, which operate in private markets and may face increased vulnerability in a prolonged high-interest-rate environment.

Future Trajectory

The consensus of FOMC policymakers was to anticipate two or three interest rate cuts in 2024. That came at the most recent update on March 20. However, since then, inflation has come in hotter than expected, causing concern that it may not be on track to meet the Fed’s 2% annual target as soon as hoped. Others argue inflation improvements have stalled. Currently fixed income markets expect to see one or two rate cuts in 2024.

Currently, the Fed is taking a wait-and-see approach. They are looking for back-to-back favorable inflation reports to commit to any rate cuts. In recent meetings, Powell has emphasized his belief that interest rates are already at peak levels for this cycle. Therefore, the trigger for rate cuts is inflation cooling further as the FOMC generally expects, or, perhaps, a reaction to a weakening jobs market.

Summary

Three years ago, the Federal Reserve implemented near-zero interest rates to stimulate the economy during the pandemic, leading to a surge in inflation. In response, the Fed raised interest rates. Despite the economy’s continued strength and inflation remaining above 2%, the potential risks associated with prolonged high interest rates cannot be ignored. Hence, the next two months are crucial as they will shed more light on the Fed’s trajectory towards rate cuts and whether we’re heading for a smooth landing or a more intricate scenario of stagflation dynamics.